As a multidisciplinary artist, doing visual art helps me out of the ruts I get stuck in with long form writing. As an artist who sometimes struggles to access or enact my vision, switching from one genre to another can open locked passageways which link the creative and literal sides of my brain. As I began the latest revision of my memoir, it felt like access to the voice I needed was hidden behind a door in a hallway of portals. This image gave me an idea to explore and I decided to use a blank accordion drawing book to help clear my mind. Each day I opened the book to an almost blank page, with just a little bit of the previous day’s color crossing the boundary between pages. Drawing helped bridge the gap between ideas and the written word in order to enter the writing and editing process. In this essay, I will detail my recent experience editing my memoir and talk about the importance of balancing visual and written work.

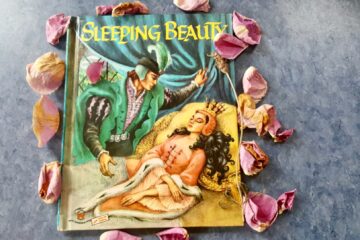

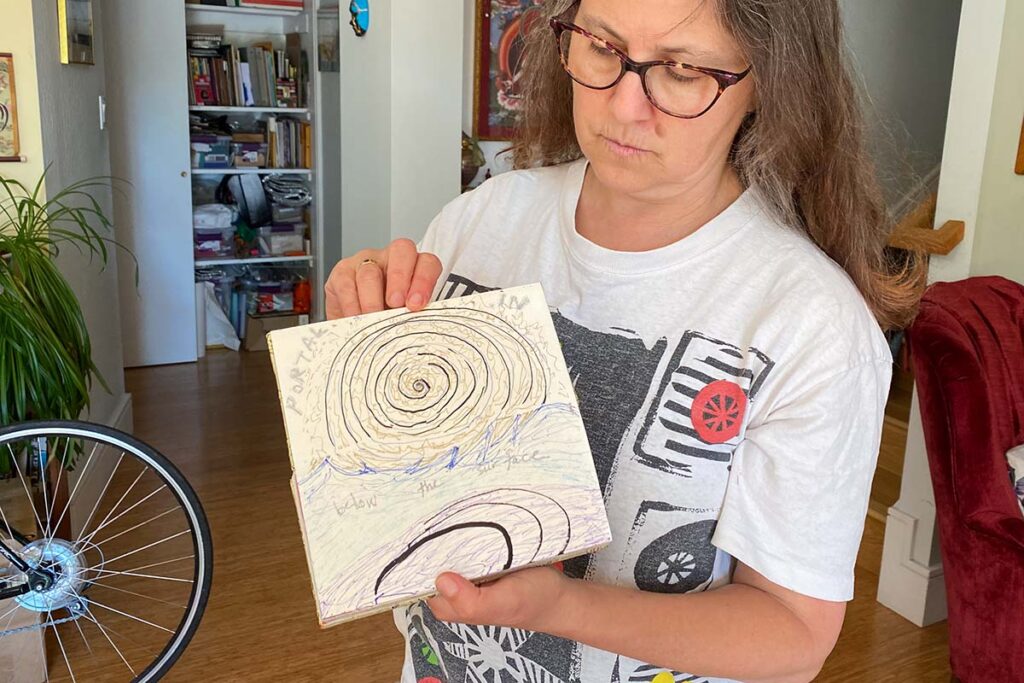

Before I even began this revision, I decided to externalize the imagined portals in hopes that it could help me to enter the memoir. On the first page, “Portal In,” swirls coil inward and outward. This double direction of spiraling allowed for symbolic entry, like an eddy of whirling water with an undefined destination. With this first invitation to enter the unknown, I began to let go of expectations. By loosening my rational grip on language and my conscious effort to fix the problems I faced in the text, I was able to tunnel toward the center which then seeped onto the next page. The experience helped to calm the pressure of decision-making I had felt, thereby enabling me to let the text speak.

Once in, I was able to explore and revise, helping me to navigate the manuscript more fluidly. I could take my time noticing and adjusting how the language felt and whether or not it was eliciting the intended feelings. I began to find ways to insert backstory into the text, which gave more resonance and shape to the evolving narrative. Metaphoric thought allowed me to enter the trance-like space of artistic flow. Herein lies the connection between the literal historic aspects of memoir, and the conceptual, metaphoric qualities of me as an artist.

By the time I reached the middle panels, I was challenged by trying to transform these lived experiences into objective stories. Questions arose about why this might be important to anyone other than me, and how to best translate my history so that it could be universally relevant. This brought me directly to thoughts about my physical and emotional connection to the stories.

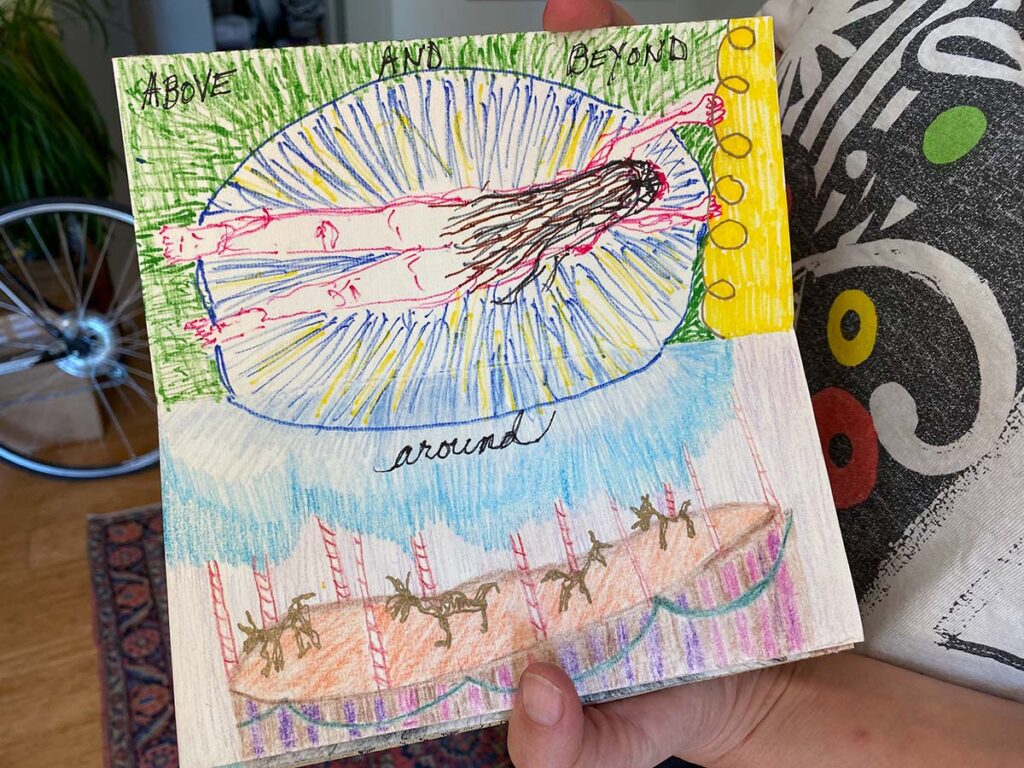

In this mid-accordion panel, suspended across a chasm, or a shaft of light and dark, clinging to the coiled gold from yesterday’s picture, a naked pink body with graying hair floats above the vortex. I carried the past into the future and created a more objective story from my memories. Floating, flying, and holding on to the through thread as I absorbed what was below the surface also gave me a sense of the objective possibility of these hard earned stories.

Alas, the further into my revisions I ventured, the less enjoyment I seemed to be getting from the process. Considering the fact that this is a project I chose to do, I could not figure out how to dismiss the part of me that felt like it was drudgery. Then, with the circle that descended from the page above, the dome-like canopy of a carousel appeared. Like the circling ride, my work cycled round the same ideas. No matter how many times the merry-go-round spins past the same view, or plays the same cycling song, there is a sense of joy and discovery in the ride. Here, in “Around” the directionality of narrative is dismissed. As I circle and cycle, the information I am riding with, the symbolic joyful ride of transformation, is revealed through this whimsical picture.

Often, the questions ‘Who am I?’ And ‘How do I see myself?’ arise, particularly as my character evolves through my narrative. How do I clearly and honestly present myself, and at the same time how do I reflect on who I was and who I have become? Self-portraits are dispersed throughout my journals and sketchbooks. Self-reflection and mirroring can be useful techniques for regulation before entering a creative zone where linear realities, like time and space, can easily get distorted. In this drawing the dangling blossoms from the previous page have caught my eye. In the process of working through my memoir, and including backstory where it offers insight into the choices I made, it was necessary to consider connections in new ways, to maintain a sense of awe and newness despite having lived and relived the same stories for many years. Maintaining a sense of wonder and drawing an imagined reflection of myself in wonderment, offered me access to the unedited emotions of experience.

Although I had not quite gotten through the whole text revision when I reached the end of the first side of my accordion drawing book, I could easily open the document to work. The voice I had been seeking had become more clear. At the final portal a flowering arbor arches across a vanishing pathway. In accepting the invitation to enter this drawing, while still maintaining the emotional stability it takes to write, I had come to a balanced place. I was able to process the historical facts and the emotional work of integrating that history in order to make something new and worthy of sharing.