I have grappled on and off with pain for much of my life. As a teenage dancer my low back hurt me persistently and I eventually had to stop dancing altogether during college, a deep loss as I had been accepted a year early as a dancer. And so it continued throughout my young adulthood, sometimes with severe sciatica, sometimes stiff joints, and an endless search for better ways to manage, heal, and return to my body. Even after leaving medical school, when I eventually became a masseuse and applied my understanding of anatomy, as well as discomfort, to ease others’ pain, my aches did not completely cease. And so, as I neared my 50’s and began the umpteenth round of physical therapy for neck pain and my chronically unstable low back, just as my menstrual cycle sputtered and my energy flagged, I hoped for relief. When the young PT said, “We need to awaken your abdominal muscles,” I questioned why part of me had gone to sleep, and what it would mean to awaken now, middle-aged.

As I began to locate my core, those forgotten abdominal and pelvic muscles, cautiously so as not to throw out my low back where so much tension was stored, I also began to write poems about Sleeping Beauty. It dawned on me that she had slept for 100 years, and I embarked on research into her age-old story in order to understand better what it meant to fall into a decades-long sleep. I also considered how I wanted to awaken into a new narrative. Although I was in love with my husband, I wanted to create a story that did not depend on a charming prince kissing me back into the world.

Thus began an extended period of reading stories and writing poems about how Sleeping Beauty, and I had fallen asleep, slept for so long, and then awakened. After her celebrated birth into a royal family, her father, the King, chose to hide her because an omen predicted harm when she became a teenager (arrived at menses). According to one legend, the King threw a feast after the birth of his daughter and had twelve gold plates made for the table, thereby excluding a thirteenth fairy. This maneuver by the King coincided with the shift from the lunar to the solar, or Gregorian, calendar. Discarding the moon calendar, which corresponds with the twenty-eight day cycle of menstruation, he removed the very idea of his daughter’s powerful transition into womanhood.

I have often wondered why we don’t teach children, or maybe teenagers, about how these bodily cycles really work. How they are timed and if you track the timing you can manage the shifts in feeling the hormones enhance. If we already knew what to expect about our moods before they rushed through us, that knowledge would be the ultimate power, true consciousness. It took me until I reached my thirties to fully appreciate the regularity of my cycle and to be able to anticipate my mood shifts with the tides. The young princess was denied the natural cyclic experience and thereby, like the enraged fairy, her own empowered rage.

The left-out fairy godmother cast a curse which the invited fairy godmothers could not negate, but did lessen it so that everyone in the kingdom would fall into a deep slumber along with the teenaged girl. Upon hearing this, the King banished all spindles from the kingdom in order to cancel the threat. The rage and curse of the wicked fairy godmother represent feminine power which is often excluded from the male dominated projections about how women ought to behave. These behaviors are also typical of the premenstrual and menstrual emotional lability that cycle with the moon. If over all of the years during which I grappled with mood swings, fought with my loves or felt despondent, I had been guided into the tides of my own body and taught how to anticipate the oscillations, so much misery could have been avoided, or at least comprehended and processed. But I had to figure it out, which I did, in part, through writing regularly.

The King’s restrictive rules about her exposure to danger do not quell Sleeping Beauty’s curiosity. When she encounters an old woman spinning in a hidden room in the castle she enters the room, touches the spindle which pricks her and the bleeding girl falls asleep. With the start of menstruation, as we enter our childbearing years, we often encounter the seductive compulsion to procreate, or in more contemporary life, to avoid procreation while exploring sexuality. Despite the inherent dangers of exploration the transition from girlhood to womanhood occurs. By internalizing the perils and the power, a complicated dichotomy is born.

In the story, sleep accompanies womanhood, and this trance-like sleep lasts for what might seem like a hundred years. In another version of the story, as the princess lies sleeping, a king from a nearby realm rapes her and impregnates her with twins. Upon the birth of the babies, when they root for her nipple, she awakens. The mythology of the awakening potential of motherhood is both ubiquitous and antithetical to self-discovery, as well as a burden for the children born to mothers who look for themselves in their offspring. While giving birth and raising a child offer profound transformational opportunities, it is hardly a way to discover and realize the curious, naive, true self the young girl left behind. Not only is the woman’s body no longer independent, but her mind is also absorbed outside of herself. This loss of singularity makes the road to autonomy and self-expression all the more challenging, despite the deep satisfactions that accompany parenting. Unearthing a balance takes a great deal of strength and many years.

I wrote about how she fell into her sleep as curiosity crossed paths with sexuality just as she had begun to search for approval outside of herself. Memories of my teenage self, embodied as a dancer and later felled by back pain, seemed to make more sense as the powerful defense mechanism of a disengaged persona also came into focus. In order to cope with the collision of expectation and desire, shutting down the gentle curiosity of my playful explorer-self made some sort of sense. This was neither an unconscious sleep, nor was it deliberate, but a trance-like self which could continue forward into a world that demanded focus and determination, but eschewed process and contemplation. This dream-like state staved off access to a deeper connection with a core sense of self from which creativity evolves, and allowed me to hide that aspect while I pursued what seemed appropriate. Also, the schism between the active, sexualized and empowered self, and the passive, sleeping and receptive self are supported by a world in which a woman is expected to be receptive, not a generator of passion. By staying asleep her own impetus is subdued. The idea that she remains beautiful and appealing without an engaged, pro-active self presents us with a long instilled, problematic paradigm.

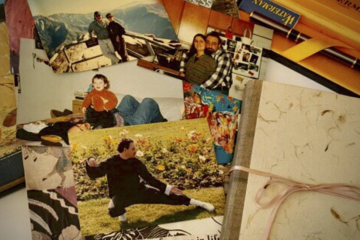

The years I spent in a somnambulant state, searching for a self I believed was inside, were arduous and tangled. Climbing out of a castle, even one built out of self-protection, can be a daunting challenge when the lure of the dream-like state feels safe. Whether through dependency or rebellion, it was often easier to avoid the terror of the cavernous, shut-in self than to find a way in to recover it. In the midst of that sleep, as time wore on, the biological urge or imperative to have a baby arose. In many ways, the decision to get pregnant was part of the dream life. The idea that a baby would offer focus, help regulate my schedule, and give me a purpose I had not yet fulfilled through my own work as a writer, was true. The demands of parenthood enforce a regulatory structure if we pay attention to the needs of the baby. Eventually, school and activities for the child continue to provide that external structure. However, as profound and satisfying as the mother identity proved for me, it did not fulfill the manifestation of self for which I yearned. The opportunity to show up as Mother offered yet another cover for the undisclosed self, without satisfying the quest to emerge.

Nevertheless, as my child developed, my effort to model strong self-reliance by investing in my own growth was essential. As difficult as it was to emerge from the long sleep I had accepted, I began to gain strength. My ability to appreciate the life of metaphor allowed me to gain physical strength as a way to revitalize my confidence. This slow process had various phases of success and defeat, but each chapter reinforced a fundamental will to thrive. Whether gaining muscle at the gym, first in gentle stretch classes with elderly gym clientele, and later in ballet body building classes, or by completing my master’s degree in writing and doing public readings, the drive to become ever more myself evolved. Although I wanted a partner, and was absolutely thrilled to meet my now husband, the idea that my own awakening would occur through falling in love felt intrinsically wrong. All that had fallen asleep inside was clearly mine to awaken.

In my version of the Sleeping Beauty story she awakens middle-aged. Although her back sometimes aches, and she can’t jump without peeing, her physical strength and awakened abdominal musculature are as accessible as her own voice. By writing her awake, through the varied phases of climbing out of the dream state into which she had fallen so early on, I was able to process the lived experience of self-gestation. In copious journals I tracked and reflected on the repeating dynamics, as well as the sputtering wane, of my cycle. Through poetry, I articulated and discovered the multiple expressions of self that had actually accompanied me across time. The birth, which occurred post-menopause, has fewer bursts or waves, and when they arise, I recognize them. Perhaps the cycles have gotten longer and accompany the seasons more than the tides. And although this middle-aged Sleeping Beauty sometimes falters, she no longer hides.